Angers, September 28th 2025

I’ll do my best to catch up on the day later, but for now I need to capture Margaret. There is no tomb. Like so many monuments it was destroyed during the revolution, or at least that’s what I think happened. Somewhere it said that when the tomb was opened to observe her parents’ Rene and Isabelle’s remains, Margaret’s bones weren’t there. So who knows what happened. All I know is she was originally interred in the cathedral so coming here to pay my respects is the best I can do. And as I write that I realise I have said that a lot recently and probably will again many times, and it feels like I’m making an excuse. Sorry Isabella, and Matilda, and Margaret, but that’s the best I can do. The best you deserve. And it isn’t. You all deserve so much more and when I think about you singly or collectively, I am overwhelmed by your strength, your courage and your fortitude. I am almost half-way through the consorts and they are, to a woman, sacrifices on the altar of wealth, power and glory. They were traded to simpering boys and gangrenous old men and the fact that not one of them took their own life is a testament to their strength of character, and I’m sure sometimes, their sheer spite. These women are uniformly great and I’m starting to feel that my poor blog just isn’t enough. I’ve been reluctant to commit to a book because there are so many biographies, but I also think that my approach, as an act of homage rather than historiography, may be necessary.

But back to Margaret. She was a force. Inevitably beautiful and appropriately educated, and so nearly married to another man only for her destiny to swerve violently towards Henry VI. Who was, let’s be honest, quite possibly our worst king. At least men like Henry VIII and Richard II fully inhabited the throne and their kingship, for all their madness and megalomania. Henry VI just wanted everyone to get along. Margaret arriving weak from the channel crossing and requiring aid and shelter while she recovered probably tapped into his romantic streak, and his presenting himself to her as a messenger is characteristically childish. History (and Shakespeare) suggests she was lovers with the Earl of Suffolk, but I think it more likely he was just the man on the ground as she made her way through France to England, tasked with educating her about her new life and acting as a link to Henry, more of a surrogate father and teacher than lover. Early in her tenure the Duke of Gloucester, Henry’s former regent and bête noir of Katherine of Valois, is arrested and probably murdered. He could have been a formidable enemy, so its likely for the best to clear the board and start fresh with whole new formidable enemies like York and Warwick. Did she look back fondly later in life to those days when all she had to worry about was court intrigue and being a source of hatred to her citizens for the loss of Anjou and Maine? Such petty trifles. Because after that, it was relentless, bitter, vicious war.

After various crises and Henry showing just how inept he could be, he eventually slips into catatonia, and Margaret, conscious of her value and rank as mother of the heir to the throne, puts her articles before parliament demanding she be made formal regent, have the right to appoint to the main seats of power, and confidently expects a smooth transition of power to herself, as would almost certainly have happened had this been France. Her mother raised and led an army, all Margaret was asking was to rule. She was the queen, it was what she had been brought here to do. I don’t think they laughed her out of parliament, but there were plenty of men who were frustrated by Henry’s dithering – and, you know, no talking or moving or even blinking for several months – and they couldn’t afford the uncertainty of another regency. Better to have a man with a strong track record and (possibly too) impeccable blood-line at the head of the country. The Wars of the Roses didn’t really start with York over-reaching, or even with the first Battle of St. Albans. You could say it was inevitable and had really already been rumbling on for years.

Henry awakens like Sleeping Beauty and acknowledges his son Edward, to Margaret’s relief, and then 6 months later the historical starting pistol is fired. St. Albans goes to the Yorkists, as, awkwardly, does Henry and Margaret is censured by parliament for being the instrument of her people’s suffering. She does her best to maintain influence, putting her men in positions of power and shoring up her base. She performs as peace-bringer at Henry’s ridiculous Loveday Pageant, though I best she scrubbed the hand that York had held. There are various courtly skirmishes with York and Warwick, though no outright violence until Blore Heath goes to the Yorkists, and a month later Ludford Bridge to the Lancastrians – though I prefer to say Angevins, since Henry had a habit of being captured, or shot, or just sitting out the action under a tree having a little pray. Margaret stays close to the action, usually at a church nearby, never in the melee but still quite clearly in control. in 1460 the Yorkists take Northampton and Margaret is forced to flee to Scotland and the protection of her sister queen Mary of Guelders. She is likely still in Scotland for the Battle of Wakefield at which York and his son Rutland are slain. She didn’t crown York with paper (silly Shakespeare) but she did order their heads be mounted on pikes outside the city. Let it be known, this is what happens to those who oppose me. There is no straight narrative here, there are wins and losses on both sides, and neither side is gracious. When Margaret wins she preens, she is effusive in triumph, and when she loses, well, she really loses. Her mistake not to take London after the 2nd Battle of St. Albans probably, in the long run, cost her the war. Did she fold because she was approached by women, appealing to her softer side? A week later the Yorkists crown their own king, Edward IV, and Margaret is left on the back foot essentially for the rest of her life.

[A bit later – I finished my lunch at the creperie and didn’t want to linger so now I’m outside the castle. I think if Botticelli had built a castle, it would have looked like this]

Acting as Henry’s ambassador, Margaret takes Edward to France and prevails upon her uncle Louis XI for help. Eventually, after councils and pow-wows and keeping Warwick on his knees for 15 minutes in anticipation, she is convinced to reconcile with him, as the king-maker has become disillusioned with the king he made. In honour of the bargain, Margaret marries her son to his daughter, Anne Neville. Margaret’s position now is difficult: she is still personally fighting for her king and his heir, but England has a new king, so she’s lost the moral, and national, high ground. She is now attempting a coup d’etat. For 16 years she has been a machine. Through every defeat, every mistake, every problem she has forged a way for herself and her family because when she was a girl that is what she was taught. There is no way her mother Isabelle or her grandmother Yolande could have known what she would face but it also doesn’t matter what the details were. She was taught, and she was shown, what a wife should be, and she took that lesson and let it grown inside her until her purpose as wife and mother was everything. That didn’t make her soft. She wasn’t ‘just’ a wife and mother. She was a Wife and a Mother, or her husband and son but also of her country. It was her foundation for every action, which meant that when she lost, she lost everything. in 1471 at the Battle of Tewkesbury, her only child Edward is slain and she is captured at nearby Deerhurst, She is paraded through London as the spoils of war at Edward IV’s triumphant return. The same night that she is imprisoned in the Tower, Henry is mysteriously murdered (reportedly by ‘melancholy’) and she is sent into captivity at Wallingford Castle, with a former friend as her gaoler. Eventually her ransom is paid by Louis XI and she is packed off back to France, as long as she gives all her remaining property to the English and French crowns. She came to England as a penniless girl of 15, and returns as a penniless and broken woman of 46, forced to accept the paltry pension of 6,000 livres and left to rot in the castle of Dampiere-sur-Loire, quite literally since it’s reported she dies of leprosy. She dies in 1482, alone, having outlived everyone of consequence to her. If only she could have held on for another three years, she would have seen the death not only of Edward IV, but the murder of his heirs, and the defeat in battle of the last of the Yorkist line, finally annihilated by the young upstart Tudor.

So, having learned what I have and written what I have, who is she in the end? Femme fatale? Warrior queen? A power-hungry women who didn’t know her place? She was a fighter. A tough and resourceful daughter of tough and resourceful mothers. She gained nothing from her marriage to Henry, because whether she were queen of England, duchess of Anjou or simply Margaret, that resilience and intelligence was always there. Whatever her purpose, she would have done it fiercely and resolutely. I see her villainous moustache-twirling in victory. I see her emptiness, her utter destruction in defeat. And I see how for 26 glorious yet blood-soaked years we as a country were her purpose, to be moulded and shaped by her remarkable resolve. Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England, I honour you.

The Life of Margaret of Anjou (or what we know of it)

Again, there are some issues with the differing calendars of France and England, and in particular the details of Margaret’s progress through France on her way to England to be married are a bit of a mess, with her seemingly doubling back on herself a couple of times. Take it up with the record keepers!

1430

- March 23: Margaret is born to Isabella, Duchess of Lorraine and Rene of Anjou, King of Naples at Pont-a-Mousson. Margaret is baptised at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Tours, with her maternal grandmother Margaret and Louis, King of Naples standing as godparents. Her nurse was Theopaine le Magine, from her grandmother Yolande’s court. [13]

1431

- July 2: Margaret’s father, Rene of Anjou, is captured at the Battle of Bulgneville and held prisoner for several years by the Count Antoine de Vaudemont, Duke of Burgundy, in a disagreement over Rene’s inheritance of Lorraine. Margaret’s mother Isabelle negotiates his release, apeealing to the Holy Roman Emperor and the king, as well as raising an army to engage with Vaudemont [2, 3, 13]

1434

- August 26: Margaret’s maternal grandmother Margaret of the Palatinate dies [13]

1435

- Margaret’s mother, Isabelle, leads an army to conquer Naples, leaving her children with their grandmother Yolande of Aragon. It is believed that it is from Yolande, as well as her mother, that Margaret learns how to exert power as a woman [2]

1436

- November: Margaret’s father Rene is released from captivity and travels to Saumur to visit with her and her grandmother [13]

1437

- April: Margaret is present with her father Rene at Angers for the marriage of her brother John of Calabria [13]

1440

- March 23: Margaret’s 10th birthday

1442

- November: Margaret’s grandmother Yolande of Aragon dies, and Margaret returns to her mother’s care. [2]

1443

- February 4: Margaret’s marriage contract to Charles, Count of Neves is signed at Tarascon, outlining 50,000l dowry and the inheritance of Sicily, Provence and Bar to go to Margaret’s children. The marriage is delayed by the Count Vaudemont while the king deliberates the legality of the union [13]

1444

- April: Margaret’s father Rene meets with William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, to discuss her marriage to Henry VI. The dowry was controversial, in that she would bring no money and take around £3k a year in revenues from the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall as well as direct from the Exchequer, her entire journey and household would be paid for by England, the counties of Maine and Anjou would be returned to French control, and the English would support Rene’s claims to the crowns of Majorca and Menorca on behalf of Margaret [3, 4]

- May 4: Margaret is present as the Earl of Suffolk and his council meet with her father Rene to discuss her marriage to Henry VI. A papal dispensation is provided by Peter de Monte as both Margaret and Henry are descended from John II of France [13]

- May 23: Margaret marries Henry VI of England at the church of St. Martin in Tours, with William de la Pole, the Earl of Suffolk standing as the groom’s proxy. The wedding is officiated by the papal legate Peter de Monte and attended by the bride’s family and the King and Queen of France. The ceremony is followed by a grand procession, a banquet at which Margaret is treated as the Queen of England, and an Arthurian tournament [2, 3, 11, 13]

- November 13: Margaret is at Caudebec-en-Caux on her way to Rouen by boat [13]

- December 12: Margaret is at Vernon from where she travels to Honfleur. The party remains there while her father Rene lays siege to Metz, which ends in March 1445 [13]

- December 25: Margaret’s marriage settlement to Henry VI is executed [11]

1445

- March: Margaret sets out from her home towards England with a retinue of c.1500 attendants, paid entirely by Henry VI as her father Rene was penniless. The Earl of Suffolk lays out more than £5k for her travel and expenses. He brings with him from England 5 barons, 17 knights, 65 esquires and 174 valets for an estimated travelling time of 91 days, though this would end up being extended to 182 days. Among the ladies to become Margaret’s household are Alice Marchioness of Suffolk, Alice Countess of Salisbury and Beatrice Countess of Shrewsbury [2, 3, 11, 13]

- Mid-March: Margaret is presented with relics in Paris, and is formally handed over to the care of the Earl of Suffolk at St. Denis. Her party then sails up the Seine towards Rouen [3, 7, 11]

- March 18: Margaret arrives at Pontoisse, the border between English and French lands [13]

- March 19: Margaret pauses her journey in Mantes to distribute alms and clothing to the poor [13]

- March 24: Margaret enters Rouen where she is met by the Duke of York, Henry’s regent in France, and is presented with a hackney and saddle from Henry VI. It has been suggested that Margaret was too ill to take part in the formal entry to the city, and her place is taken by the Countess of Salisbury or Shrewsbury wearing Margaret’s betrothal gown [3, 7, 11, 13]

- March 31: Margaret visits the abbey at St. Georges de Boscheville [13]

- April 1: Margaret has reached Pont-Audemer, moving on to Honfleur the following day [13]

- April 8: In advance of Margaret’s entry into London, the commons council orders all roofs and window lattices to be reinforced as it is likely people will stand on them to catch a glimpse of her [7]

- April 9: Margaret’s ship, the Cok John, accompanied by a fleet of 55 ships lands at Portchester, but having seen terrible seas and lost both masts, Margaret has to be helped ashore to a nearby cottage where she passes out from sickness. She is also locally described as being sick with smallpox [3, 11, 13]

- April 14: Margaret meets her husband Henry VI for the first time, at Portchester Castle. Henry dresses as a page and brings a letter to her, escorted by the Earl of Suffolk. Margaret has him wait on his knees, and while she reads Henry observes her, believing this is the best way to view a woman. It is only after he departs that Suffolk tells her that had been the king [2, 3, 13]

- April 16: Margaret has not yet recovered from her channel crossing, so Henry VI writes that he will not attend the Garter Celebrations in London so her can remain with her [13]

- April 23: Margaret marries Henry VI at Titchfield Abbey. Henry has the ruby ring he had worn to his French coronation remade into Margaret’s wedding ring. The marriage is presided over by William Ayscough, Archbishop of Salisbury, who would later be dragged from his church and murdered during Cade’s Rebellion: a special dispensation is been granted allowing them to marry during Lent, and the 128th Psalm is one of the readings. As a wedding present, Margaret is gifted a lion, which costs 65s 4d to transport to the royal menagerie at the Tower of London [1, 7, 13]

- May 28: Margaret arrives at Black Heath and begins her formal entry into the city of London [3, 7]

- May 30: Margaret is crowned queen of England at Westminster Abbey by the Archbishop of Canterbury John Stafford. She wears a white damask dress decorated with gold, and a gold and pearl coronet on her loose hair. She also wears the Ilkyngton Collar, gold set with rubies, sapphires and pearls with a diamond pendent which cost £4k. The pageants surrounding her coronation focus heavily on her being a peacebringer, as well as her maternal duties. [1, 3, 13]

- June 12: Margaret and Henry VI are at Canterbury as part of their first royal progress [13]

- December 17: Margaret writes to her uncle Charles VII of France to say she would do all she could to convince Henry VI to release Maine back to the French. 5 days later Henry VI also writes to Charles VII, agreeing as a favour to Margaret. It is a very unpopular move as it had been won by Henry V. In exchange for Maine, Renee offers a lifetime alliance to Henry VI and a 20-year truce through Charles VII’s ambassadors [2, 4, 7]

1446

- February 10: Margaret and Henry open parliament in Bury St. Edmunds [3]

- February 18: Margaret’s steward, Viscount Beaumont, arrests Henry VI’s uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, on suspicion of treason. Five days later he is found dead in his cell [3]

- February 24: Margaret receives £333 6s 8d from estates in Lancaster after the execution of the Duke of Gloucester [11]

- September: Margaret visit’s Becket’s shrine at Christchurch, Canterbury, which has associations with fertility [7]

1447

- September: Margaret visit’s Becket’s shrine at Christchurch, Canterbury, which has associations with fertility [7]

1448

- March 2: Margaret is on her estates at Pleshey in Essex, from where she writes to Edith Bonham, prioress of St. Edward’s Abbey of Shaftesbury in Dorset regarding the rectorship of Corfe Castle and its bestowal on her chaplain Michael Tregury [10]

- March 18: Margaret writes to the three executors of the will of Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, asking them to provide alms from the estate to a poor couple, W. Fruter and Alice Knoghton to enable them to marry [10]

- March 23: Margaret’s 18th birthday

- April 15: Margaret issues letters patent founding Queen’s College in Cambridge ‘to conservacion of oure feith and augmentacion of pure clergie…and to laud and honneur of sexe femenine’. She is the first queen to sponsor such an institution [7]

- July 24: Margaret is granted taxes levied on wool and woolen products passing through Southampton, London and Kingston on Hull [12]

- December 16: Margaret requests that Geoffrey William, a page of her kitchen be granted two mills and their watercourses in Abertive in South Wales, in lieu of lands in Ireland which he will forfeit [12]

1449

- July: Margaret’s uncle Charles VII of France declares war on England [4]

1450

- March 23: Margaret’s 20th birthday

- July: Margaret and Henry VI take refuge at Kenilworth Castle as the Jack Cade rebels reach London with their manifesto [3]

- October 24: Margaret begins a correspondence with the sheriffs of London regarding Alexander Manning, who has applied to her for her influence in helping him keep his job as keeper of Newgate jail. He had been summarily dismissed after allowing prisoners to escape during a riot. The sheriffs essentially ignored her first letter, and after a second, they reviewed his case and found him still ineligible. A year later she tries again, but Manning is never reinstated and her interference does nothing to endear her to the city administrators. [10]

- November 5: Margaret permits by letters patent for the Convent of Wix in London, part of her dower lands and in her advowson, to elect a new prioress after the death of the former prioress Katherin Welling [10]

1451

- December: Margaret and Henry VI spend Christmas together at Eltham [13]

1452

- February 28: Margaret is granted a collection of lands and rights as part of her dower, including: the manors of Devises and Marlborough, parts of the rentals of farms in Northampton and Queenhithe in London, a smaller part of the rates from two watermills under Oxford Castle, rents from the nearby meadows and fisheries, and rentals from farms in Scarborough and Waldegrave. [12]

- December: Margaret and Henry VI spend Christmas together at Bella Court, Greenwich, Margeret’s home which was granted to her from the Duke of Gloucester’s estate on his death [13]

1453

- January 1: Margaret gives a gold tablet engraved with the image of an angel to the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham. On the same day as part of her New Year gift-giving, she gives 66s 8d to the servants of both the dukes of York and Somerset. It is possible she gave the same amount to both men’s households as a conscious statement of her neutrality [7]

- January 5: Margaret is present with Henry VI at the Tower of London for the investiture of Henry’s half-brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor as the Earls of of Richmond and Pembroke respectively [13]

- March 6: Margaret’s failure to conceive after 8 years of marriage leads to a parliament being convened at Reading where Henry VI’s half brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor, sons of Catherine of Valois and Owen Tudor, are legitimised [13]

- Spring: Margaret makes a pilgrimage of thanks to the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham on discovering she is pregnant [2, 7]

- April: Margaret is staying in Norwich during her visit to the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham: while there she attempts to arrange a marriage for Elizabeth Clere, a wealthy local widow. Clere, despite being summoned in person by Margaret, choses to remain unmarried and in sole control of her estate [10]

- July 21: Margaret is granted by parliament full royal judicial rights on her estates and a life right to all moveables forfeited to the king. It has been suggested that this was a ‘reward’ for finally getting pregnant [7]

- August 15: Margaret’s husband Henry VI suffers his first serious attack of paralysis, remaining uncommunicative and unable to move for many months [2]

- September 10: Margaret is conveyed by water to Westminster by the mayor and aldermen of London, dressed in scarlet, for her lying in. She is accompanied by the dukes of Somerset and Buckingham [7]

- October 13: Margaret gives birth to her first child, a son named Edward, at Westminster, and the Duke of Somerset and Duchess of Buckingham stand Godparents as his baptism, officiated by the Bishop of Winchester. Edward is created Duke of Cornwall at his birth. Margaret immediately has her household moved to Windsor Castle to be near Henry. Her son is presented to his father twice but Henry fails to respond, leading many to believe that Edward is not his child [2, 3, 6, 7]

1454

- February: Margaret presents a bill of articles to parliament; she claims the regency for herself, that she would have the power to appoint the chancellor, treasurer and holder of the privy seal, as well as other high offices of the shires: it is not known what her fifth article was, but it has been assumed it would have been custody of her son. This is defeated and the Protectorate is granted to Henry VI’s cousin, the Duke of York. He is granted 2k marks a year for this position, but Margaret’s rights and possessions are explicitly protected from this [2, 3, 7]

- March 15: Margaret’s son Prince Edward is invested as the Prince of Wales and created Earl of Chester. His investiture comes with the revenues of the principality of Wales, to the Prince, or in his minority whoever controls his household, which at this time is Margaret, giving her some measure of financial security. It is not clear if this was the specific reason for his early investiture, but it was a concrete outcome. [6, 7]

- December: Margaret’s husband Henry VI regains consciousness and recognises his son. The protectorate is removed from the Duke of York and the couple returned to London [2, 13]

1455

- May: Margaret and her household move to Greenwich for safety while Henry VI travels to Leicester to hold parliament. Henry’s train is attacked by the Duke of York at St. Albans, the Duke of Somerset is killed and Henry is taken prisoner and returned to London. Margaret retreats with Prince Edward into the Tower for safekeeping. This attack is widely seen as the first military engagement of the Wars of the Roses. In the same month, Margaret discourages parliament from paying the outstanding wages of the garrison at Calais, totalling £40k. This leads to the Earl of Warwick beginning to pay them out of his own pocket so they will continue fighting French attacks on the city [2, 3, 5, 9, 13]

- July 24: Margaret is censured during parliament, with Yorkists supporters declaring the country had been ruled ‘by the Queen, the Duke of Somerset, and their friends had been of later a great oppression and injustice to the people’. [13]

- October 8: Margaret is with Henry VI at Hertford Castle as he confirms the appointment of George Neville as Bishop of Exeter [13]

- December: Margaret and Henry VI spend Christmas at Hertford Castle [13]

1456

- March: Margaret is escorted out of Coventry with the same ceremony as the king, shocking onlookers, which is apparently done as the city council had been informed she would be displeased if she was not shown this respect [7]

- May: Margaret and Prince Edward leave London and remove to Tutbury in Staffordshire. It is possible this was as a result of York’s removal from the protectorate or it may have been out of necessity to check on her land holdings. [7]

- June 7: Margaret and Prince Edward are at Chester. By the end of the summer Henry VI would join them. [7]

- June 15: Margaret travels to Coventry to see the Corpus Christi pageants, but asks to enter quietly with no formal ceremony. While there she is given, among other victuals, 300 loaves of white bread by the mayor and council [7]

- August: Margaret and Prince Edward meet with Henry VI at Kenilworth Castle as she tries to influence him against the Yorkist threat, removing his men from the positions of chancellor and treasurer and appointing her own supporters. This is likely in response to warnings directly to her from the Dukes of Somerset and Buckingham that the Duke of York, though having resigned his Protectorate, still harbours ill will towards Henry. [3, 13]

- September 14: Margaret is received into Coventry in advance of a Great Council meeting. The speeches and plays focus heavily on her role as wife and mother, rather than wielder of authority [7]

- September 20: Margaret, Henry VI and Prince Edward are at Coventry [11]

- September 24: Margaret’s chancellor Lawrence Booth replaces Thomas Lisieux as keeper of the privy seal. This is widely seen as Margaret’s influence to minimise Yorkist sympathisers in positions of power [7]

- October: Margaret attends the Great Council at Coventry where it is said the Duke of York leaves the king on good terms but not the queen [7]

- December: Margaret, Henry VI and the court remove to Leicester and large quantities of canon are removed from the armoury in London to Kenilworth Castle [8]

1457

- January: Margaret and Henry VI are at Kenilworth, having spent more than a year absent from London. While there, the royal master of ordnance is tasked with upgrading the castle’s defences, including shipping in 294lbs of gunpowder, 1,200lbs of sulphur and 1800lbs of saltpetre [13]

- January 28: Margaret’s son Prince Edward comes under the tutelage and guidance of a council of lords, including Margaret’s former chancellor William Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester and her chief steward John, Viscount Beaumont. They are to act ‘with the approval and agreement of our best beloved consort the queen’. This also gives Margaret control of the income from lands in Wales, Chester and Cornwall, and expands her control of land considerably. [7]

- March: Margaret, Henry VI and the court move to Hertford Castle [13]

- March 26: Margaret’s son Prince Edward is granted a licence to issue charters and writs in his own right, though he is only 3 years old [13]

1458

- March: Margaret takes part in Henry VI’s ‘Loveday’ pageant, progressing through London to St. Paul’s hand in hand with the Duke of York, intended to bring together the warring factions of his court and council, and demonstrate their friendship to the people [3]

- Easter: Margaret and Henry VI are at St. Albans for the holidays. [7]

- May-June: Margaret and Henry VI return to Margaret’s palace at Greenwich [13]

- September 10: Margaret and Henry VI return to St. Albans [13]

- November: Margaret’s men clash with the Earl of Warwick’s at a council meeting after she attempts to have the Earl arrested for piracy. Following the incident, the earl fleas the country for Calais [5]

1459

- April: Margaret keeps an open house in Cheshire and distributes badges of the swan emblem to supporters [11]

- May: Margaret, Henry VI and their son Prince Edward travel again to the north to Coventry and Leicester. As they travel, Edward gives out silver badges shaped as swans to visitors granted a personal audience with him. Margaret orders 3k bows for the royal armoury [3, 13]

- June: Margaret indicts the Yorkist lords who fail to attend a council meeting at Coventry, who claim it isn’t safe for them to attend [13]

- September: Margaret is with her son Prince Edward at Eccleshall when she hears of the Earls of Warwick and Salisbury marching towards her. She rallies her force of 8,000 men under Lord Audley, and they meet 10 miles from her location at Blore Heath. Margaret’s forces are routed, and her having given the order to attack first exacerbates Yorkist feeling towards her [13]

- September 23: Margaret is said to have observed the Battle of Blore Heath from the nearby church of Mucklestone and ordered the shoes on her horse to be reversed to cover her tracks as she escaped the Lancastrian defeat. However, that church would have been behind the Yorkist line so at least that part of the legend is untrue. [5]

- October 12: Margaret is likely at Eccleshall with her son Prince Edward as Henry VI opposes the Yorkists at Ludford Bridge, who flee before the battle can even begin [13]

- December 11: Margaret is specifically named (most high and benigne Princesse Margaret the Quene) in the oath of allegiance sworn by 66 peers to Henry VI and his son Prince Edward [10]

- December: Margaret, Henry VI and their son Prince Edward spend Christmas at Leicester Abbey [13]

1460

- March 23: Margaret’s 30th birthday

- May: Margaret and her son Prince Edward are likely reunited with Henry VI at Coventry after his southern progress [13]

- June: Margaret remains with Prince Edward at Coventry while Henry VI and his supporters march on London to confront the Earl of Warwick’s forces who have invaded from Calais [3]

- June: Margaret and Prince Edward flea to Harlech Castle after the Lancastrians forces are defeated by the Yorkists at Northampton. Henry VI is taken prisoner. In their flight they are deserted by their guard and robbed of all their belongings [2, 4]

- July: Margaret and Prince Edward are set upon in their retreat from the Battle of Northampton by Lord Stanleys Men, but are rescued by a 14 year old squire named John Coombe of Amesbury. They make their way eventually to Harlech Castle [10, 11]

- October 24: Margaret’s son Prince Edward is disinherited of the throne by an Act of Accord, which allows the Duke of York and his heirs to succeed to the crown after Henry VI’s death [13]

- December: Margaret arrives by ship in Scotland with Prince Edward. They are the guests of Mary of Guelders at Lincluden Abbey in Dumfries, and she it is here she hears news of the Battle of Wakefield, at which the Duke of York and his son the Earl of Rutland had been killed [10, 13]

- December 31: Margaret’s forces defeat the Yorkists at Wakefield, during which the Duke of York is killed, and his brother the Duke of Salisbury is summarily executed after the battle. Margaret is said to have put a paper crown on York’s head, though this has no basis in fact. However she does order the heads of the two men to be put on pikes at the gate of York city. Margaret is elsewhere reported to still be in Scotland during the battle [2, 3, 10, 11]

1461

- January: Margaret is in Dumfries, staying for at the abbey of Lincluden with the Scottish Queen Mother Mary of Guelders and the infant James III [11]

- January 20: Margaret is in York, where she issues a proclamation that as she and her son Prince Edward were beng kept from Henry VI, she calls upon every loyal man to join them in freeing the king. However, she was so keen to advance and press their advantage that her force leaves without securing supply chains and this affects her forces considerably, leading to pillaging on their route south. [10]

- February 2-3: Margaret’s step-father Owen Tudor is taken prisoner at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross, and later beheaded in Hereford [13]

- February 16: Margaret hears from a spy in the Earl of Warwick’s household that he is encamped north of St Albans, allowing her to move her forces to the east and take Dunstable, and then to attack St Albans at dawn, catching the Earl by surprise and forcing him to make a tactical withdrawal. [13]

- February 17: Margeret and Prince Edward remain at St. Albans Abbey as her forces defeat the Earl of Warwick at the second battle of St. Albans. The evening after battle, Henry VI dubs their son Prince Edward a knight [3, 13]

- February 19: Margaret requests entry into the city of London but is rebuffed by a deputation of noble ladies, including Jacquetta, Countess Rivers and Imania, Lady Scales, both of whom had accompanied Margaret from France, and Anne, duchess of Buckingham who was godmother to Prince Edward, who fear the chaos the army would bring. Instead, with a large force and no local and lawful way of feeding them, she installs her troops at Dunstable. This failure to secure the capital is seen as her greatest failure, as a week later Edward of March, eldest son of the Duke of York, enters the city with the Earl of Warwick and a week after that he is crowned king Edward IV [3, 10]

- March 15: Margaret is reported to have poisoned Henry VI by the Milanese ambassador Prospero di Camulio, in order to marry the Duke of Somerset [7]

- March 29: Margaret’s forces are defeated at Towton and she, Henry VI and Prince Edward are forced to flea from York to Scotland. While there she negotiates with King James II for men and money: her opening offer is to give her son Prince Edward as a husband to one of King James III’s sisters, but the Scots prefer a more tangible bargain, and Margaret agrees to give up the city of Berwick, the northernmost English stronghold against the Scots. This is seen as almost as bad as the cessesion of Maine. Margaret is said to have offered the plunder of all lands south of the river Trent in lieu of wages for the troops [2, 3, 8, 11]

- July: Margaret sends the Dukes of Somerset and Hungerford to France to request aid from Charles VII, only for them to discover that he has died and been succeeded by his son Louis XI. [11]

- November 4: Margaret, Henry VI and Prince Edward are attainted by act of parliament, and Henry VI is labelled a usurper. The earl of Warwick is charged with overseeing a trial of murder against Henry VI, but this never comes to pass [13]

1462

- April 8: Margaret lands in Brittany as Henry VI’s official envoy to France [10, 13]

- June 23: Margaret is granted 20,000 francs by Louis XI in exchange for surrendering Calais back to the French [11, 13]

- June 27: Margaret stands as godmother to Louis, son of Charles, Duke of Orleans [13]

- September: Margaret sails from Normandy with Captain Pierre de Breze and 800 troops, evading the Earl of Kent who was blockading the Channel. After landing and re-boarding at Alnwick, 4 of her fleet of ships are destroyed by storm and the men who take refuge on the Holy Island are massacred. Margaret and De Breze escape in an open boat to Berwick [11]

1463

- July: Margaret and Prince Edward sail from the north country to France, leaving Henry at Bamburgh Castle, to set up a court-in-exile at St. Mihile-en-Bar [10]

1464

- May: Margaret’s forces are defeated by the Yorkists at Hexham Forrest. Legend has it that during their retreat they are attacked by bandits, only being released when one of them takes pity on Margaret. Margaret and Prince Edward give up their crusade and sail to France, leaving Henry VI behind to be close to the action [2, 4, 13]

1467

- May: Margaret is invited to the French court by Louis XI, but fearing she would be forced into a truce with the Earl of Warwick, who was to meet the king at Rouen, she refuses to go, although one of her ambassadors is reportedly there [13]

1468

- December: Margaret attends a family gathering cum council with her father Rene, her brother John of Calabria and Louis XI to discuss how to take advantage of crises within the Yorkist camp [13]

1470

- March 23: Margaret’s 40th birthday

- June 25: Margaret and her son Prince Edward arrive at Chateau Amboise to meet with Louis XI, who wants to convince her to ally with the Earl of Warwick and return to England to fight Edward IV [13]

- July 22: Margaret is reconciled with the Earl of Warwick at Angers at the behest of her cousin Louis XI. They agree that Warwick would restore Henry VI to his throne with French aid and in exchange, Margaret’s son Prince Edward would marry Warwick’s daughter, Anne Neville. Louis XI’s support is contingent on the English surrendering their final continental foothold of Calais back to the French. Margaret keeps Warwick waiting on his knees for 15 minutes before accepting his peace offering. [2, 4]

- July 25: Margaret’s son Prince Edward is formally betrothed to the Earl of Warwick’s daughter, Anne Neville [10]

1471

- March: Margaret, after a long delay, attempts the Channel crossing accompanied by Sir John Longstrother, leader of the Knights Hospitaller, but is beaten back by the weather [13]

- April 9: Margaret makes a second attempt to cross the Channel but is beaten back again [13]

- April 14: Margaret finally lands at Weymouth with her family and a reported 8,000 troops [13]

- April 18: Margaret, Prince Edward and his wife Anne Neville land in England and almost immediately flee to Cerne Abbey in Dorset. On the same day, Warwick is killed in a battle against the Yorkists and Edward VI removes Henry VI from the palace back to the prison [2, 4, 5]

- April 30: Margaret is at Bath, marching with a reported 40,000 troops (but probably more like 6,000) towards London when she hears of Edward IV’s approaching forces, and instead of waiting to engage them she moves north west, heading for Wales [13]

- May 2: Margaret is at Berkley Castle. The next day her forces are denied entry to Gloucester by Edward IV’s men, so she moves on to Tewkesbury. Margaret herself, along with Anne Neville and Lady Courtenay, takes shelter in the small religious house of Deerhurst close to Tewkesbury Abbey, leaving her son Prince Edward to prepare for battle [11, 13]

- May 4: Margaret’s son Edward is killed at the Battle of Tewkesbury, and buried at Tewkesbury Abbey [6]

- May 7: Margaret is discovered at Deerhurst by Edward’s IV’s forces and puts herself ‘at the king’s commandment’ [11]

- May 21: Margaret is displayed as part of Edward IV’s celebratory entry into London. She is imprisoned in the Tower of London. On the same day, her husband Henry VI is murdered, probably in Wakefield Tower. He is buried at Chertsey Abbey, and later removed to St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. At the time, his death is given as ‘melancholy’ [4, 6, 10, 13]

- July: Margaret is moved out of the Tower of London to Windsor, and then to Wallingford Castle, in the custodianship of Alice, Duchess of Suffolk, where she will remain for three years. She is given 5 marks per week for her upkeep and servants. [13]

1475

- August 25: Margaret’s cousin Louis XI agrees to ransom her for the sum of 50,000 marks at the Treaty of Picquigny between himself and Edward IV. Louis grants her a pension of 6k livres, but only on the cessession of Anjou, Provence, Barrois and Lorraine back to the French Crown, and her lands and rights in England to the English crown [2, 10, 11, 13]

1476

- January 29: Margaret is formally freed from captivity, sailing to Dieppe accompanied by Sir Thomas Montgomery, and is handed over to Louis XI’s men at Rouen. She takes up a pensioned residence at Reculee. As part of her ransom back to France she is forced to relinquish her claims to Anjou and Maine [2, 4, 13]

- March 1: Margaret officially cedes all her claims to Anjou, Lorraine, Bar and Provence to Louis XI [13]

1480

- March 23: Margaret’s 50th birthday

- July 10: Margaret’s father, Rene of Anjou, dies aged 80. He leaves Margaret 1,000 crowns in gold marks on the condition she remain a widow, and the chateau of Queniez. He commits her to the keeping of a close friend, Francis de Vignoles of Lorraine who takes her to the castle of Dampierre-sur-Loire [13]

1482

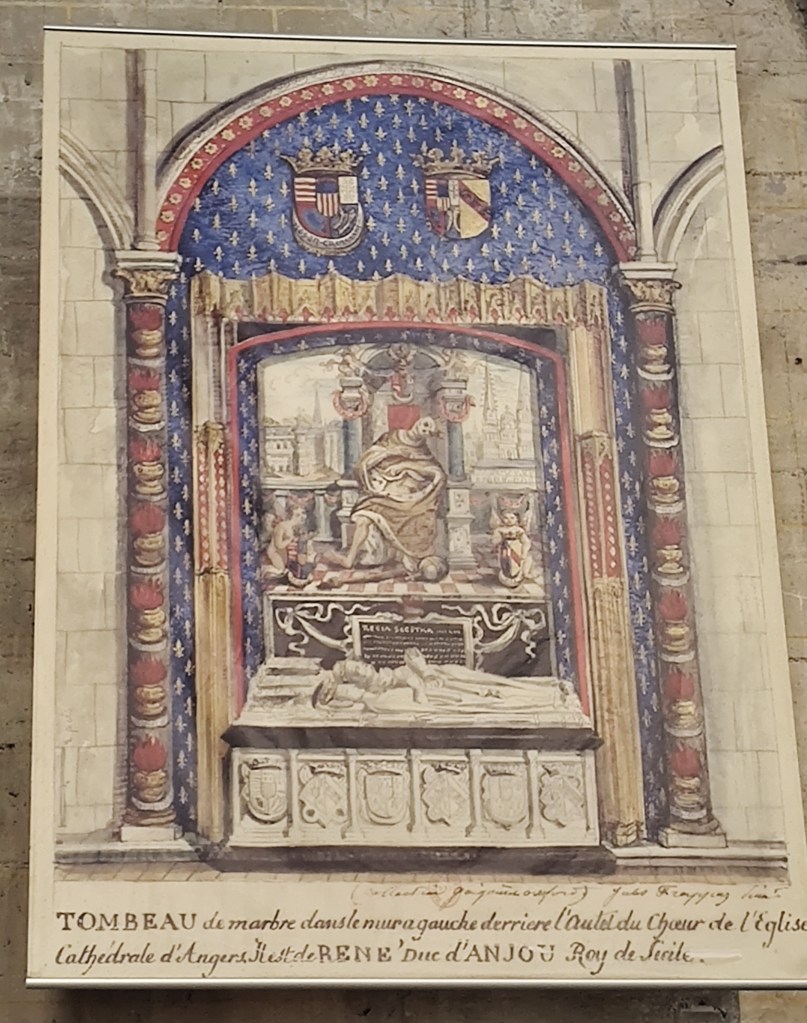

- August 25: Margaret dies at the castle of Dampierre-sur-Loire. It has been suggested she was suffering from leprosy. She is buried in Angers Cathedral in the tomb of her father, without any inscription, but she is depicted in a nearby stained glass window. A memorial in which priests progressed around her tomb on the feast of Souls continued until the French Revolution. In her will she leaves her worldly possessions to Louis XI of France. [2, 4, 13]

References

- Wikipedia [all uses corroborated with other sources]

- Norton, Elizabeth (2011) England’s Queens: the biography. Stroud, Amberley Publishing

- Hilton, Lisa (2008) Queens Consort: England’s medieval queens. Chatham, Weidenfeld & Nicholson

- Norton, Elizabeth (2011) She-Wolves: the women who ruled England before Elizabeth. Great Britain, Faber & Faber

- Licence, Amy (2013)Anne Neville: Richard III’s tragic queen. Stroud, Amberley Publishing

- Weir, Alison (2008) Britain’s Royal Families: the complete genealogy. Great Britain, Vintage

- Maurer, Helen (2005) Margaret of Anjou: queenship and power in late medieval England. Great Britain, Boydell & Brewer

- Boardman, A. W. (1994) The Battle of Towton. Stroud, Alan Sutton Publishing.

- Watts, John (1999) Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

- Maurer, Helen (2021) The Letters of Margaret of Anjou. Great Britain, Boydell Press

- Ramsay, James Henry (1892) Lancaster & York. Oxford, Clarendon Press

- Deputy Keeper of the Records (1909) Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office. London, HMSO

- Licence, Amy (2018) Henry VI & Margaret of Anjou: a marriage of unequals. Yorkshire, Pen & Sword History